Former Slovak Foreign and European Affairs Minister, Miroslav Wlachovský offers unique insights into how non-profit organizations are reshaping modern diplomacy. As a distinguished diplomat who served as Slovakia’s Minister of Foreign and European Affairs (2023), Ambassador to the United Kingdom (2011-2015) and Denmark (2018-2022), Wlachovský brings rare dual expertise from both government service and NGO leadership. His career trajectory from heading the Slovak Institute for International Affairs to advising Prime Ministers Mikuláš Dzurinda (20012003) and Eduard Heger (2018-2022) positions him uniquely to analyze the intersection of governmental and non-governmental diplomatic initiatives. In this exclusive interview, Wlachovský examines how think tanks and advocacy groups are transforming international relations in an era of complex global challenges.

From your extensive diplomatic experience, how do you perceive non-profit organizations such as GLOBSEC as strategic partners in shaping contemporary foreign policy? What unique value do they bring to the diplomatic ecosystem that traditional governmental channels might overlook?

I started in an NGO in the 1990s called the Research Center of the Slovak Foreign Policy Association before I joined the Foreign Service. I always had great respect for the work of NGOs because I think they can provide unique platforms for meeting people. They are perceived as more independent and not biased by partisanship. I believe it is true that they are perceived like that, but I think that, in reality, most of them are keen to keep their neutrality and non-partisan character, and some of them, during their existence, have created quite a strong name for themselves. GLOBSEC is one of those organizations. It started almost 20 years ago as a student conference, and today it is a global conference. It’s a global security conference in Central Europe, much respected, and out of that project, some other projects have also started to develop. So, today, GLOBSEC is what we call the Central European Think Tank with global ambition. It’s not just a conference; there are other events we organize throughout the year. We publish papers on different kinds of foreign policy issues, but also on health and other issues that are very much related to international affairs.

Can you elaborate on specific instances where non-profit research and advocacy have meaningfully influenced foreign policy decisions in Slovakia or within broader European diplomatic frameworks?

Sure, I can give you one example. Most recently, we published a paper on what should be the program of the new European Commission from the perspective of Central Europe. We had a discussion about it in Brussels and in some papers. It was created from a broad range of experts from Central and Eastern Europe, and I think it is crucial in this time of challenges before the European Union when we really need to reform some parts of how the European Union is working. I think the influence of Think Tanks is exactly in that field, where you raise the issues and suggest possible solutions or ways to approach certain policies.

Many argue that non-profit organizations are becoming increasingly critical in international relations. Based on your experience, what structural advantages do non-profit organizations have in addressing complex geopolitical challenges that government institutions might find challenging?

It’s an excellent question, and I think I partly answered it in response to your first question because what is attractive about a non-profit organization is that they can create a platform where even controversial or not generally accepted ideas are discussed. What they have as an advantage over the government, I think, is their network of connections and cooperation with other similar institutions in other countries, which helps a lot. If you create a network of Think Tanks and nonprofit organizations focused on certain issues, it’s very helpful, and it provides a mirror to government policies in a country but also in a broader region.

How do non-profit organizations serve as crucial intermediaries in diplomatic dialogue, especially in scenarios involving complex international tensions or emerging global challenges?

I can give you an example from the past of GLOBSEC when I was not connected with the organization but was cooperating from a different angle. I know there was one of the GLOBSEC forums in Bratislava where we actually managed to invite both the Greek Minister of Defense and the Turkish Minister of Defense. It was during a period of real tension between the two countries, and it was in Bratislava where they informally sat down and discussed certain things. Since then, their dialogue started to grow. Conferences like this provide this umbrella for different kinds of meetings, even for people who usually would probably not meet or would find it difficult to arrange. Under this umbrella, it is possible, and it can create new opportunities, as it did in this case between the Greek and Turkish Ministers.

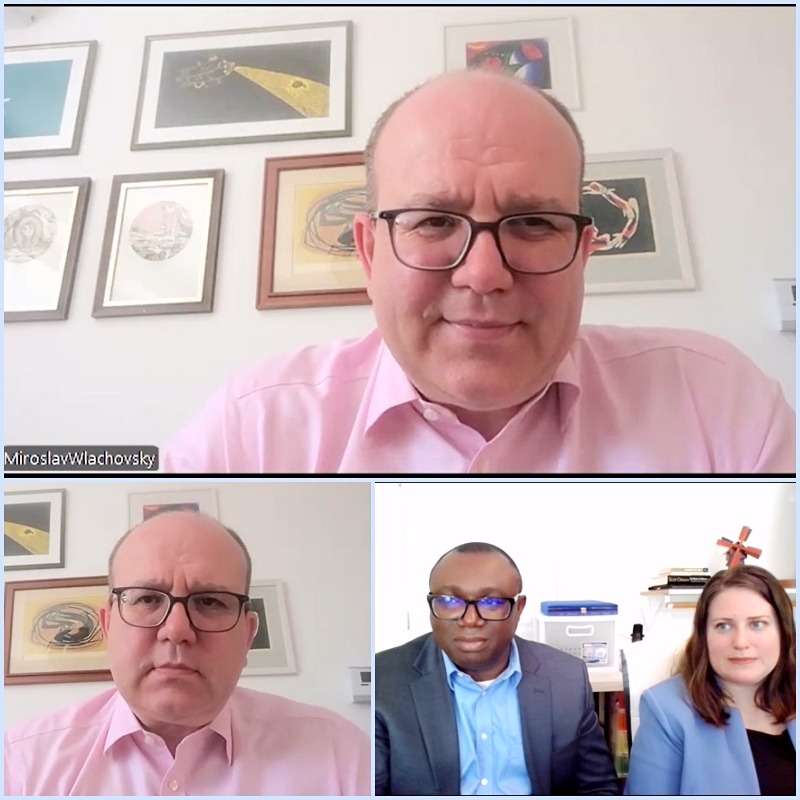

Credit: Photo Supplied

Credit: Photo Supplied

In your view, what are the most significant limitations and opportunities for non-profit organizations in directly contributing to foreign policy development and implementation?

When it comes to limitations, they are obvious. It is always a question of resources and money— how to fundraise, how to get support from either state organizations or private enterprises. That is always a challenge for any kind of non-governmental organization, no matter how big or famous it is; it is always a challenge. Limitations are also evident when it comes to inviting people and creating cooperation. It’s not like you create an NGO and all people will come because you just created an NGO. You have to earn their respect, earn their trust, and prove yourself valuable by bringing added value to what they can achieve. You really have to convince your partners that you bring this added value; otherwise, your enterprise can fail.

Drawing from your roles at the Slovak Institute for International Affairs and the Research Center of the Slovak Society for Foreign Policy, how do Think Tanks and non-profit research organizations fundamentally transform the landscape of foreign policy formulation?

There is one important aspect of non-profit organizations: they bring foreign policy issues closer to the general public. The general public usually is not that concerned about foreign policy issues. They are much more concerned about the economy and day-to-day business. We brought foreign policy issues to life through our publications and events. This is extremely important, especially in the current world, where we are very much interconnected, for people to understand how foreign policy actually influences their lives and the impact it can have on their day-to-day agenda. It’s very difficult to explain this and to bring knowledge about the foreign policy agenda to the general public.

How can non-profit organizations effectively bridge the communication gap between governmental foreign policy objectives and public understanding, particularly in an era of increasing global complexity?

I fully agree with you that there is a gap, and I think that non-profits can be used as a tool of soft power vis-à-vis the general public. This means they can cooperate with the government on certain issues—how to bring information and knowledge about foreign policy issues to the general public through different kinds of events. In cooperation with the government and other countries, this is how government and non-governmental organizations can collaborate on issues of mutual interest. This was the case in my country for many years. From government resources, we provided support or partially supported some activities of NGOs. They matched resources by finding ways to get support from foundations or private sources, and together, because we were able to identify common goals, they proceeded and helped us spread information and convince the general public about Slovakia’s foreign policy priorities. There is good space for government and non-governmental organizations to cooperate on such issues if there’s a will on both sides.

Looking forward, what strategic investments or transformations do you believe non-profit organizations need to make to remain relevant and impactful in shaping future foreign policy landscapes?

First of all, like any other organization, non-profits must ensure their survival. They need resources to run their programs and pay their employees. They also need to find the best way to network on advocacy issues, whether regional or global. It’s always good when they can communicate and push together on some of these issues. They must also fundraise for campaigns and gatherings. It’s important to find the right communication tools to influence both the general public and policy spheres, as well as to network people for a common goal. This is challenging due to the scarcity of resources and the era of disinformation. Many NGOs are victims of disinformation and smearing campaigns, making it a difficult environment.

Being the former Slovak Minister for Foreign Affairs, how were you able to navigate the complexities of working with other non-profit organizations while in office?

We are a rather small or medium-sized country, so it’s not that difficult to know the key actors in the nonprofit sector. We were in contact with all of them. We had a special program where they could apply for grants concerning foreign policy, either from the angle of foreign policy events or possible challenges and problems we needed to research. If their project was successful, they received modest government support. That’s how we cooperated. Of course, sometimes it was difficult to explain to some that they didn’t get the resources that others did, but that’s life. In general, I think we managed to have very productive relations between the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of Slovakia and the NGO sector.