The Washington Educational and Cultural Attaché Association (WECAA) meeting at the Ronald Reagan Building last Friday wasn’t just about Swizz Ambassador to the United States, H.E. Jacques Pitteloud’s speech. The real dynamism unfolded during the Questions and Answers (Q&A) session, as the Ambassador and audience engaged in an intellectually stimulating exchange of questions and ideas while exploring profound topics.

Nelson Garcia, the founder of the Washington Intergovernmental Professional Group, kicked off the conversation by speaking about a topic close to his heart: language learning. He expressed concern about the stark difference between the United States, where foreign languages are often introduced only in high school, and Switzerland, where students begin their linguistic journeys as early as 7 years old.

Ambassador Pitteloud, who is equally passionate about languages and speaks several of them enthusiastically endorsed Garcia’s point. He went beyond simply supporting the idea of early language learning.

He stated emphatically, “Languages are fundamental. They are fundamental because very soon you will have applications that you will be able to speak to someone from Kazakhstan or from Papua New Guinea in their language, well actually in Papua New Guinea they have 50 languages so that may be some time. But in any other language you will be able to make yourself understood. And to understand what the other person is saying. But this is not the same. Because speaking and understanding a language is understanding the Soul of the Nation and this is really it.”

He countered the misconception that Americans are somehow limited in their ability to learn languages. He pointed out that “here in America where people will usually tell you “oh, you know I have to apologize I am American I speak only English. I don’t accept this. The American brain is not wired differently than ours. And it’s a matter of the decisions made to not know. And I would push foreign languages more.”

Ambassador Jacques then made a compelling case for promoting foreign languages in schools which displays the intellectual flexibility and cultural enrichment they bring.

The conversation shifted gears when a representative from the Global Peace Education Network posed a critical question: How can we integrate peace education skills into the curriculum?

Ambassador Pitteloud’s response was both personal and powerful. He spoke from his own experience, having witnessed the devastating consequences of hatred and prejudice firsthand during a genocide. With a deep sense of urgency, he called for the dismantling of those very forces through education. He lauded Switzerland’s public education system, where students from diverse backgrounds are brought together to learn from each other, not just from textbooks.

He added that “school is the best integration and the best peace education. It’s instrumental. We have in Switzerland, in the same school people from Serbia and Kosovo. People from Turkey and Kyrgyzstan. They have to live together. They have to learn the same language. They have to abide by the same rules. They have to accept the existence of the other guy. Up to the point that they even have to speak to them and realize that they are even humans.”

This intermingling, he argued, fosters understanding and becomes a powerful tool for promoting peace.

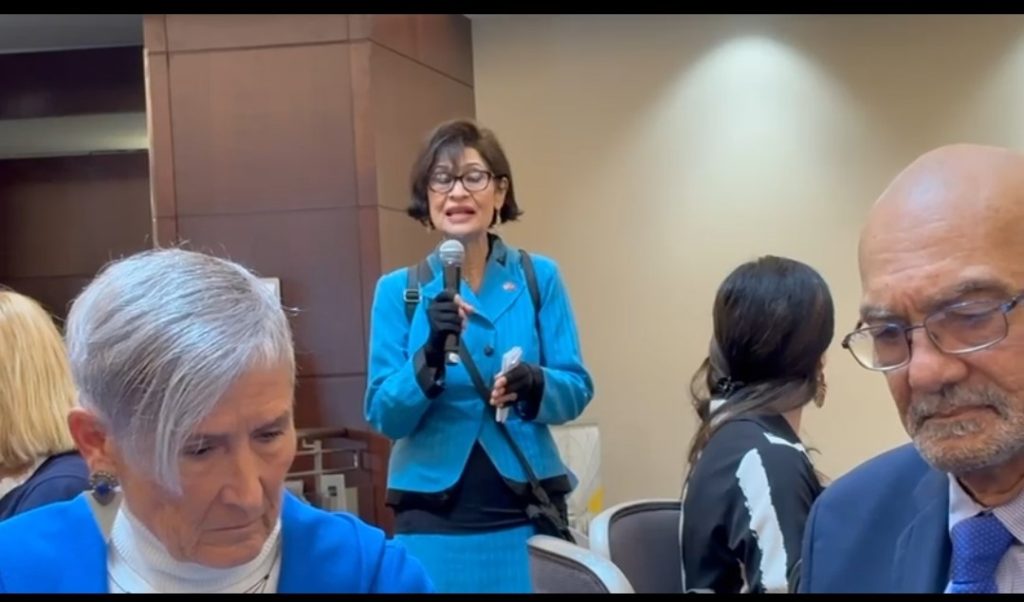

Letisha Malcolm, a Fulbright Scholar and Global Exchange Coordinator for the Council Of International Education for DOS-CIEE, brought the conversation to a more practical level. Her question focused on potential apprehensions Africans might have regarding global exchange programs. Ambassador Pitteloud acknowledged a lingering trend; African students often favor former colonial countries for higher education. However, he offered a convincing alternative. He highlighted the benefits of considering Switzerland, particularly for English speakers who could leverage their existing language skills to seamlessly integrate into the academic environment. This, he suggested, could open doors to new experiences and challenge preconceived notions.

Andrew Kutt, the founder of the Oneness-Family Montessori School, which prioritizes foreign languages from a young age, took a different approach. He sought the Ambassador’s viewpoint on building connections across cultures. Ambassador Pitteloud, offered a simple yet thoughtful piece of advice: “In a nutshell, I will tell you what I tell young diplomats. How to be a successful diplomat. Drop your national lens. You are in the U.S., the trains are not on time, which means that there are no trains. That’s fine. You are not in Switzerland. Accept the fact that you are in the U.S. and try and look at what they do better than we do. And if you are Italian in this country they call this brownish brew coffee, you know what real coffee is. But that is fine. You are not in Italy. So, drop your lens. That’s the first connection, it’s to try to really understand. Secondly, learn the language if you can.”

He therefore advised listeners to shed their preconceived notions about other cultures and approach them with genuine curiosity. As for language learning, he reiterated its importance but added two more crucial elements to the mix: love for humanity and appreciating the positive aspects of each country. By embracing these principles, he recommended, building bridges instead of walls.

The final question came from an Afghan American who offered an emotional story of her home country. She expressed concern about the state of education, not just under oppressive regimes, but also in established democracies like the United States.

Ambassador Pitteloud’s response was a candid admission of past mistakes. He acknowledged his generation’s neglect of educational reforms, a lapse that he now sees as a contributing factor to the current state of affairs. He again made a clarion call for the restoration of public education systems, particularly in the US. He stressed the need for a system that gives priority to quality and inclusivity, ensuring that every child, regardless of background, has access to a robust education that equips them to be successful and engaged citizens of the world.

In conclusion, the Q&A session with Ambassador Pitteloud transcended the typical diplomatic back-and-forth. It was a dynamic exchange that explored the critical role languages, education, and a willingness to embrace differences can play in developing a more peaceful and interconnected world. The audience did seem to have left not just informed but inspired to take action and advocate for positive change in their spheres of influence.